Modern industrial and post-industrial societies are increasingly relying on the scientific method for advancement of economy, citizen well-being and even culture. This shift from a more intuitive or, some would say, primitive way of thinking and decision making has undoubtedly benefited human race by accelerating technological progress and giving us an instrument for revealing the truth about the world in an unbiased manner. This understanding of universal usefulness of science is illustrated by the fact that most developed countries invest a great deal of money into various scientific programs without any obvious economic incentive. The explanation for that being the fact that long term positive effects of scientific development far outweigh the contemporary encumbrance of having to support costly research infrastructure. This atmosphere of increasing rationalization seemingly leaves little place for art to be of any significant value in the modern world.

This simplified view of the world, however, ignores major limitations of the scientific method. One being it’s focus on falsifiability, which in conjunction with technological limitations of our times effectively precludes the application of science to most of imaginable questions. Another big problem is the fundamental inconsistency of the mathematical framework that is at the heart of all modern science. This surprising quality discovered by Kurt Gödel in the first half of the twentieth century demonstrates a fundamental flaw in our understanding of logic and shows that no amount of technological or theoretical progress will provide us with a fully consistent view of the world. At the same time there are less metaphysical problems stemming from overspecialization. While overall scientific knowledge consistently grows, the fraction of it that can be internalized by any given person shrinks day-by-day. Each field grows deeper and deeper in it’s understanding of the subject, develops new jargon and narratives. As a result it is often a challenge to effectively communicate this information between the members of different fields, let alone between the scientists and general public.

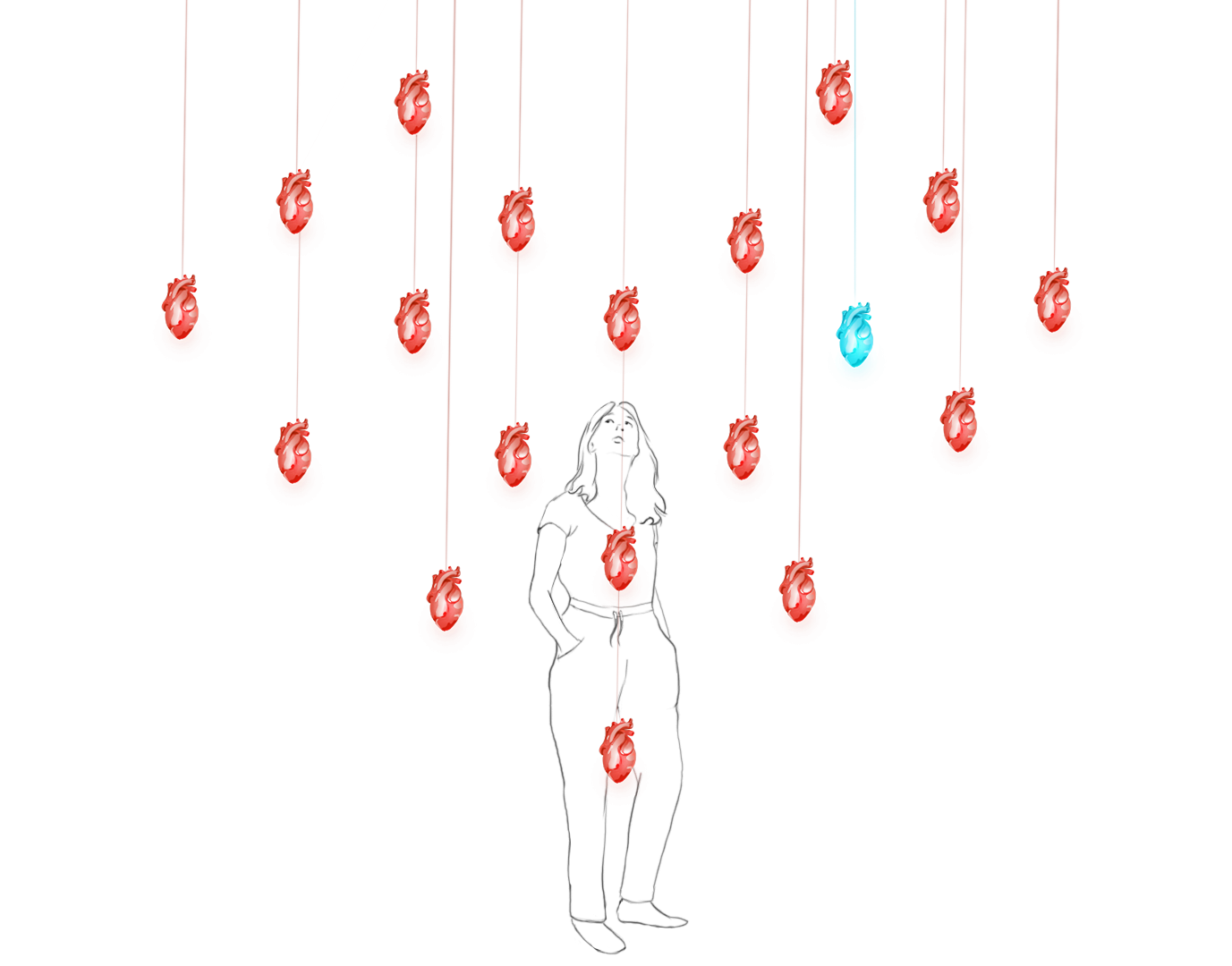

But even if there are some cracks left to fill, could art be of any use in this endeavour? After all, art often serves a utilitarian function: as simple decoration, meaningless distraction, a profitable investment, a communication tool, at best a medium to share empathy and facilitate psychological support (nothing a future anti-depressant or anxiolytic can’t handle much more easily). The problem of overspecialization is also quite prominent in the art world. As any art form develops in it’s own rich historic and cultural context it acquires (deliberately or otherwise) footprints of the past: references to historic events, callbacks to previous works of art, callbacks to the aforementioned callbacks and so on and so on. A resulting work of art can become overburdened with information that without a substantial prerequisite knowledge is unreadable. To put simply, for a layman these pieces of art make as much sense as a physicist droning for hours about tensor products.

So, is there a role that art can play to help us with our understanding of reality? Does it need one? That I simply do not know. But being involved in the Enhancer in Art project I’m hoping that the process will help me to judge for myself.